At a time like this where the coronavirus pandemic has forced us into isolation, it would make sense to watch Contagion, a movie that chronicles the spread of a new virus and its immediate aftermath on society. But Todd Haynes’ 1995 film, Safe, not only does this on a microscopic level with a lone protagonist, it is much more reflective of this year’s politics.

The very first impression that Carol White—played by Julianne Moore—gives off is that of a jaded wife. No dialogue is required when a minute into Safe, we see Carol in bed with her husband, Greg (Xander Berkeley) having sex. The framing of this sets up the story perfectly well—through a bird’s eye view, Carol’s faceless husband continues to thrust his body while Carol stares at the ceiling. Our eyes go to Carol’s face as her lifeless expression conveys so much—more than any other verbal exchange between the two would. After her husband “finishes,” she gives him a kiss on the cheek, a sort of protocol-ish way of saying “good job, you’re the man.”

Safe tells the story of Carol, a homemaker who leads a mundane life within the suburbs of San Fernando Valley. It’s clear when we follow her through the day that the term “homemaker” can be applied loosely. Besides ordering furniture or going to the cleaner’s, she doesn’t have much to do because her husband is affluent enough to hire a maid that does all the cooking and cleaning. And so, she fills the gaps within her days by attending the gym, accompanying her husband to luncheons, and meeting with the other dolled-up housewives. Her purpose in life aligns with that of a trophy wife, but instead of donning a superficial smile, she feels empty and stilted, not fully engaging with her husband or her friends.

In the beginning of the film, it seems that we know which direction Todd Haynes is going down: the unsatisfied housewife boxed into this forever role of domesticity tries to break free. Carol White is a Jeanne Dielman. She is an April Wheeler. However, because she has her own maid and a stepson that’s already in his pre-teens, Carol is reduced to an accessory that doesn’t meet the norms of a typical mid-20th century housewife, norms that we do see in Jeanne Dielman and in Revolutionary Road. Julianne Moore embodies this with naïve eyes that makes her look lost and a high-pitched tone in her breathy voice that registers child-like innocence.

Things take a turn, though, when Carol observes signs of illness. She suffers breathing problems while driving down a polluted highway, her nose starts bleeding after getting a perm, and she suffers some sort of panic attack at a baby shower. After those around her react indifferently towards her ailments and doctors find no explanation, Carol comes across a flyer that takes her to a support group where she concludes that she’s sensitive to the chemicals that permeate her environment. Now, this takes place in 1987, a time where anxiety and depression were still relatively taboo. Today’s audience could infer that Carol must be suffering internally with an unsatisfying family life and rituals that confine her. Unfortunately, these topics of conversation are never addressed, so it’s easier to find a scapegoat like chemicals instead of confronting something that’s so blatantly obvious to audience members. Once she latches onto this reasoning behind her symptoms, there’s a certain pep to her step. While for others this illness would feel debilitating and restricting, Carol finds enlightenment with her ailments. She carefully monitors what she eats, stops applying makeup, and stops driving her car. It’s apparent through her devotion to this new lifestyle that Carol is finally able to fill the void of emptiness in her life with a newfound purpose. This purpose, however, is short-lived when her symptoms start to severely affect her immunity.

She eventually seeks treatment at the Wrenwood Center, a treatment community in the middle of the desert that encompasses the film’s third act. The center is run by Peter Dunning (Peter Friedman), who is a wealthy HIV-positive man living in a mansion overlooking the complex. But instead of promoting dialogue between its inhabitants, Dunning’s approach is to gaslight them by placing the blame of the illness onto themselves. He exclaims that, “if your immune system is damaged, it’s because you allowed it to be.” This, combined with his Orwellian rejection of outside sources (newspapers and television), is enough to make Wrenwood resemble more of a cult than a treatment facility. The fact that Carol is enlightened and inspired by Dunning’s cultish behavior only underlines her childish innocence. Her desperation for answers leaves her blinded by those who wish to take advantage of her. Julianne Moore’s reticent portrayal of Carol really illustrates the fact that rather than standing up for herself and speaking up about what’s really on her mind, Carol is really looking for another person to fill in the blank spaces for her.

What’s sad and essentially the most disturbing aspect of the film is the ending. From Carol’s perspective, she’s happier in Wrenwood than at her home in the beginning of the movie, further emphasizing the fact that her husband and suburban lifestyle were a source of her anxieties. But from the audience’s POV, this happiness seems very short-term because there’s no relief in the methods that Dunning relays onto his patients; there’s a scene where the patients are gathered in a circle and Dunning reduces one of them to tears, ultimately inflicting emotional trauma. When Carol stands in front of the mirror in her isolated igloo, she stares at her reflection and declares: “I love you.” This comes off as a temporary manifestation of what she’s been taught, but the camera suggests otherwise. Her tired eyes and bleak lighting enshrine her and point out a false resolution. She might be in a better place mentally, but for how long? After all, the camera points outs Carol’s isolation she must feel in this enclosed igloo, almost mirroring her life back in San Fernando Valley.

Considering this was made in 1995 and the film takes place in 1987, it’s easy to point out the various lenses that Safe can be viewed through. Allegory of the AIDs epidemic. History of postmodern feminism, where the repercussions of a patriarchal lifestyle are documented. Cautionary tale about the harmful effects of a chemically dependent society. However, all of these comparisons mesh into one singular narrative where the various thematic angles create an exciting and eye-opening viewing experience. Even today, its themes of isolation and inabilities to combat illness make it very pertinent to the year of 2020.

When I watch it, I find that Safe resonates in the year of 2020 because of its honest portrayal of the toxicity of tribalism. The film is an in-depth look at a woman who is essentially a victim of her own environment. And as we see her try to seek autonomy from the chains of suburban patriarchy, we simultaneously witness her fall victim to “an equally debilitating self-help culture that encourages patients to take sole responsibility for their illness and recovery.” And with that, the film evokes an appropriate question at the film’s conclusion: are we ever autonomous or are we subject to tribalism? In today’s political climate amidst coronavirus, if you deviate somewhat from certain views of your political affiliation, you are immediately ostracized or, in today’s terms, cancelled. GOP Rep. Liz Cheney was attacked by her fellow House Republicans for disagreeing with the President’s foreign policy and showing support for Dr. Anthony Fauci. If a liberal, as Bari Weiss states, is “to be anything less than Defund the Police,” they are immediately considered a “heretic.” When Carol’s physical symptoms start to show up around people within her bubble, she is greeted with indifferent stares and looks of disgust by her wealthy husband and her supposed friends. Her symptoms inadvertently challenge the status quo, which forces her to leave this tribe of affluence and white picket fences. It’s strange that with all the money that comes from her husband, she is not able to find answers and has to travel to a barren piece of land populated by not so wealthy sick people. And this new destination really points out the reality of tribalism, that one’s identity is really filtered through the lens of his or her respective tribe. It makes sense that the leader of this group is in charge of the Wrenwood Center; his intimidating label gives him the green light to prey on the vulnerable. It’s never explained whether or not Carol is actually being healed—we just need to take her word for it. And when she does explain to everyone else in the center how relieved she’s feeling, it comes off as wooden. She still speaks in her childish breathy voice accompanied by those sorrowful eyes, but it’s her pauses and stumbles that reflect the speech’s artificiality. It’s more of a nervous effort to appease Dunning and the rest of the tribe who have surrounded her with such attentiveness. And when she goes to bed that same night, we know the future looks just as bleak as her life in San Fernando Valley. Even though there’s a constant reminder from her or her husband that this retreat is temporary, she never wants to go back home, and it’s reasonable to infer that she might just stay there permanently. Her identity has molded itself for the sake of this new tribe she’s found herself in.

Safe is the last word I’d use to describe the year of 2020. From bush fires to pandemics to police brutality to incompetent leadership, it’s hard to stay calm when the world we call home is on fire literally and figuratively. It’s Todd Haynes’ Safe that perfectly captures this isolating atmosphere that we’ve become so familiar with. There’s a quality within Safe that makes it seem like it’s always levitating. From the film’s gothic space music to Julianne Moore’s appropriately subdued performance to even Todd Haynes’ unsettling yet dreamy direction, the film can still be appreciated as an intriguing work of fiction. Yes, Safe will inevitably evoke sociological questions and interpretations that pertain to today’s climate, but its execution is an achievement in cinematic storytelling that will warrant future viewings.

©Killer Films

©Killer Films Rosario Dawson as Ruby

Rosario Dawson as Ruby

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Hunters in the Snow (Winter), 1565, oil on wood, 162 x 117 cm.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Hunters in the Snow (Winter), 1565, oil on wood, 162 x 117 cm.

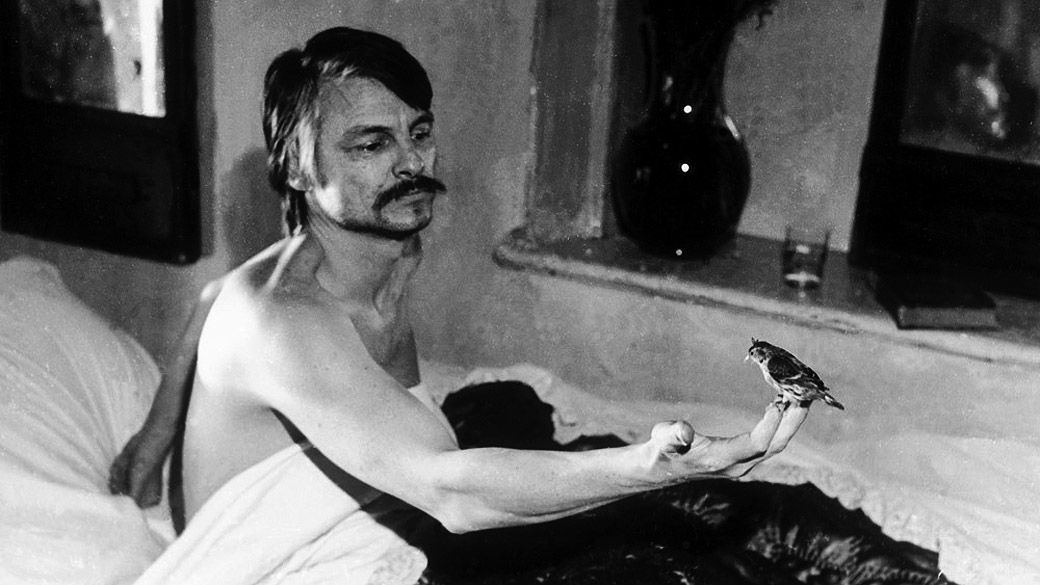

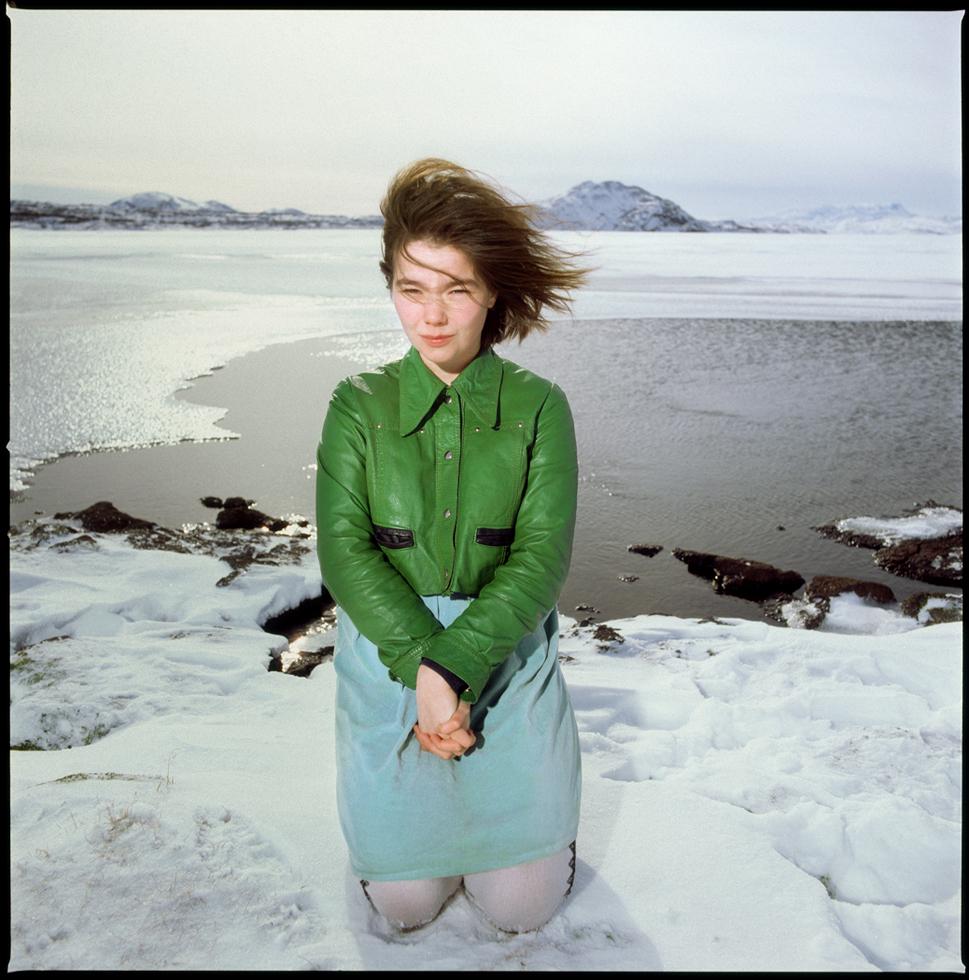

©Magnolia Pictures ©Mosfilm

©Magnolia Pictures ©Mosfilm