©Mosfilm

The prospect of writing about Andrei Tarkovsky is an intimidating one, to say the least. His films are not easily accessible for his stories possess a very non-linear structure. But he is able to get away with it due to the magic of cinema. You watch one of his films and conclude that the only way his stories can be told is through the moving image—not through writing, not through poetry, and not through theatre. It’s as if cinema was made for Tarkovsky as much as Tarkovsky was made for cinema.

What exactly comprises Tarkovsky movies? Besides a nonlinear structure that defies rules of conventional storytelling, other common characteristics include woozy montages, excessively long takes, historical film reels, symbolic imagery, and a dreamy atmosphere—as he states, it’s important to have a precise rhythm.[1] The subjects in his movies usually embark on emotional and physical journeys toward ominously unfamiliar destinations, essentially searching for some type of clarity/fulfillment; it is through these characters’ voyages that Tarkovsky poses his deeply philosophical questions about human existence to the audience. Tarkovsky films are so singular that I can’t help but chuckle when Wikipedia classifies them as Soviet films. They’re really the complete antithesis of Soviet films. If anything, they are anti-Soviet films because they abandon the norms that characterize Soviet film culture. Coming from a pair of Soviet immigrant parents myself, I’m pretty much well aware of these conventions because I grew up watching them, but to give an example: The Diamond Arm (Бриллиантовая рука). This 1969 comedic heist film is the absolute epitome of standard Soviet cinema. And what characterizes this standard? Obviously, a very linear story with an easy-to-follow structure. The color scheme is very saturated with vibrant colors, unlike the neutral–sometimes, bleak–colors of Tarkovsky’s hypnotically drawn-out shots.

A stark contrast can best be summarized by the number of cuts. Within the first half-hour, The Diamond Arm consisted of 173 shots. Compare that to Tarkovsky’s 1979 Stalker which possesses a 163-minute running time; within these 163 minutes, the film contains 142 shots.[2] And so, when Tarkovsky rejects the status quo, how does he tell his stories? He does it through nature. Through the sound of water droplets and the site of birds in flight, Tarkovsky conveys this notion that the purpose of human existence is to forge relationships that inevitably cause the manufacturing of memories which live on forever, long after death.

I think Andrei Tarkovsky most evidently captures this moral struggle he possessed with human existence within Mirror, which makes sense, considering it’s his most personal work. Up until Mirror’s release in 1975, Tarkovsky had tackled historical fiction, religious biography, and science fiction. But Mirror marked the first time where the director turned inward and tried to make sense of his life up until that point. However, it’d be inaccurate to label Mirror as a traditional autobiography. Although Tarkovsky bases most of the pivotal events in the film on his own life, he creates a fictional narrative centered around a dying man named Alexei—not Andrei—as we the viewers become witnesses to three significant time periods within the man’s life. It’d be more accurate to deem the film’s story as depicting Andrei’s visual imagination.[3]

Tarkovsky explains his intentions with his film within the first several minutes during the prologue. Here, we see a speech therapist curing a stuttering teenage boy as he ultimately declares: “I can speak!” The difficulty of personal expression for Andrei is made apparent with the boy’s stuttering, but with this final declaration, Tarkovsky is mentally liberated enough to confront elements of his life—or Alexei’s. And so, we journey with Alexei as he reflects through three distinct timeframes of his life: prewar (1935), wartime (1940s), and postwar (1960s-1970s). But because of Tarkovsky’s unique interpretation of time, the structure of the film isn’t simply a journey through the past told through flashbacks–the journey is rather intermittent and nonchronological. There’s never a clear indication of which time frame we’re watching as the story slips into and out of a period rather abruptly. And it doesn’t help matters when he casts the same actors for several pairs of key characters. For example, actress Margarita Terekhova plays not only the role of the young Alexei’s mother, Maria, during the prewar and wartime frames, but she also assumes the role of the adult Alexei’s wife, Natalia, during the postwar frame.

Terekhova as Maria; Terekhova as Natalia

While Tarkovsky loved Terekhova’s acting[4], it’s pretty evident that this was an artistic way of showing time’s omnipresence; a tongue-in-cheek moment occurs when it’s revealed that the reason why Natalia wishes to divorce Alexei is because she looks like his mother. This ties to Tarkovsky’s definition of time, which has nothing to do with history nor evolution. Instead, he describes it as “…a state: the flame in which there lives the salamander of the human soul.”[5] And how is time depicted? Through the construction of memories.

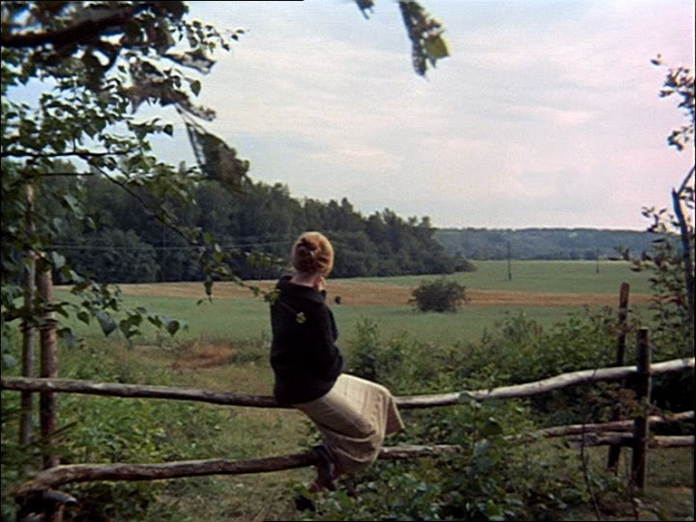

Tarkovsky implements elemental imagery in Mirror to illustrate how memories are so integral to our lives. A pretty significant example is outlined in the very shot that follows the black-and-white prologue. We cut to a young woman sitting on a wooden fence rail and smoking a cigarette as she stares out into the green field right in front of her. We eventually find out that this woman is Alexei’s mother during the prewar period as she solemnly waits for her husband—Alexei’s father—to come home. However, the way that Tarkovsky composes this image is not so casual. He approaches the back of her and all we see is her figure enshrined in an abundance of bright green vegetation.

We come to find out that the young Alexei is resting on a hammock just behind her; and so, this long tracking shot of his mother that opens the scene takes on a whole different meaning. It doesn’t just initiate the story, but it also frames a snapshot that Alexei has stored in his mind, a sight so memorable that the older Alexei is able to access it mentally and almost relish in its nostalgic beauty. The only manner in which postwar Alexei is able to access his history is through preciously stored memories—minute moments of time that have defined his existence. Tarkovsky is able to intertwine the past with the future by using an image like a burning barn in the midst of a rain shower. After the neighbors scream of their family barn catching fire, the camera pans past the barn engulfed in flames as rain pours down.

This almost creates a conflicting image as fire and water are two of the most opposing natural elements. But Tarkovsky’s execution creates an image of meditation and beauty, illustrating the synchronization of two contradicting concepts—the past and future. And just like the opening shot of Maria on the fence, we experience Alexei’s vivid recollection of this moment in time as we hear the cuckoo-clock, the glass bottle falling off the table, and consecutive raindrops coming down from the rooftop—details that showcase how much we are able to vividly recall moments of our life so effortlessly. This supports the notion that memories do not require us to mentally dig deep into the vaults of our mind in order to remember details; memories are embedded into our everyday lives. While they may not dictate our future, they exist symbiotically with our present, defining who we are and leaving behind our marks on earth.

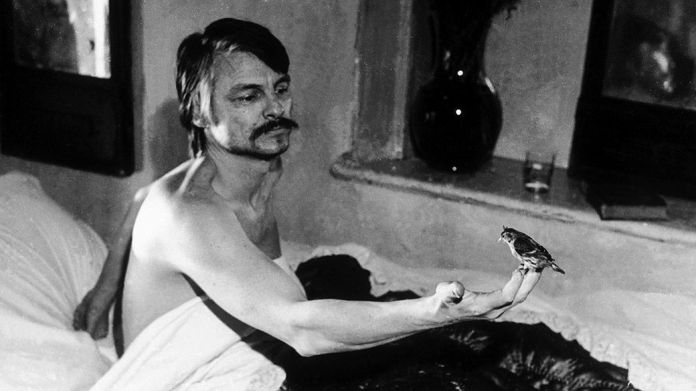

Tarkovsky’s fascination with nature also helps flesh out his idea that human existence is not only guided by memories but also the acceptance of mortality. After all, it is truly after death that our legacies will be judged by others based on the memories we’ve cultivated. Tarkovsky reflects on death in a 1978 interview, stating, “I am convinced that life is only the beginning…I just know that a man who ignores death is a bad man.”[6] Believing that life is a precursor to something spiritually beyond our physical existence, Tarkovsky uses the motif of a bird to outline this notion. During the prewar time frame, Maria and a young Alexei visit a doctor’s house, but find that the doctor is not home, and instead, they acquaint themselves with the doctor’s wife. The wife offers Maria a hen for her journey back home but tells her that she must kill the bird herself because she’s too nauseous to do it. After Maria hesitantly kills the hen, there’s a monochrome vision of a cockerel escaping the house through the window. The flapping of its wings signifies that the hen has moved onto another dimension, supporting Tarkovsky’s theory on an afterlife. This scene serves precedes the ending in which Alexei is on his death bed during the postwar era. By this point, we’ve seen Alexei reflect on his entire life and make peace with the past. Through this, he accepts his own mortality, and so, he refutes the idea that he is a bad man. He reassures his mother sitting by him that, “everything will be alright.” And as he says this, he picks up a dying sparrow (Tarkovsky’s hand is actually holding the bird) and resurrects it, setting it free as it flutters into the atmosphere—all while Alexei takes his final breath. Much like the sparrow and the

cockerel in the vision, Alexei’s soul flies away and towards whatever lies ahead. It is because of the sparrow that Alexei has come to terms with his death and fully embraces the afterlife. By this gesture, a full circle has been achieved; Alexei has embraced his memories—what defined his life on Earth—by reliving them and now his memory will live on forever.

When Tarkovsky completed Mirror, he confronted the memories of his past and was finally granted peace, causing his stress to melt away.[7] And by depicting Alexei’s death as a peaceful transition, Andrei Tarkovsky stated that he too was ready; this proved to be prophetic when the cinema maverick passed nearly a decade after the film’s release at just the age of 54. Tarkovsky’s characteristic use of vivid natural imagery continues to evoke passionate reactions from audiences today. Never one to dwell on symbols, he always knew that the viewer was the final vital piece of the puzzle. After all, “a book read by a thousand different people is a thousand different books.”[8]

[1] Tarkovsky. Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema. U. Of Texas P., 2017. Pg. 113.

[2] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0079944/trivia?ref_=tt_trv_trv

[3] Bird, Robert (15 April 2008). Andrei Tarkovsky: Elements of Cinema. Reaktion Books. ISBN978-1-86189-342-0. Pg. 1362.

[4] Tarkovsky. Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema. Pg. 131.

[5] Tarkovsky. Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema. Pg. 57.

[6] Gianvito, John (2006). Andrei Tarkovsky: Interviews. Univ. Press of Mississippi. ISBN978-1-57806-220-1. Pg. 47.

[7] Tarkovsky. Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema. Pg. 128.

[8] Tarkovsky. Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema. Pg. 177-178.